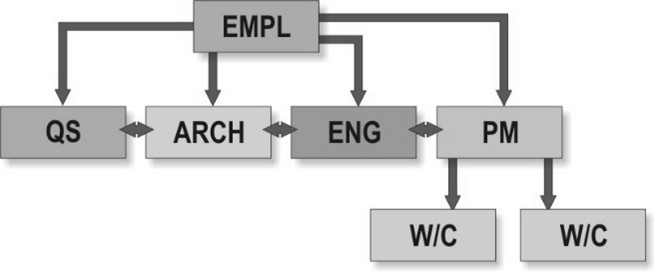

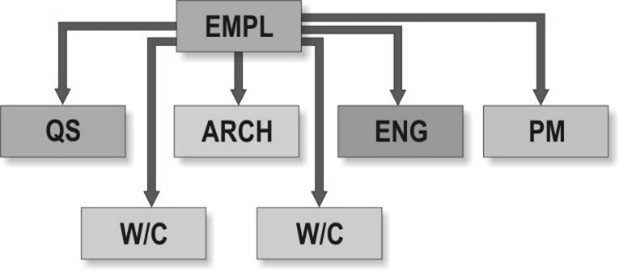

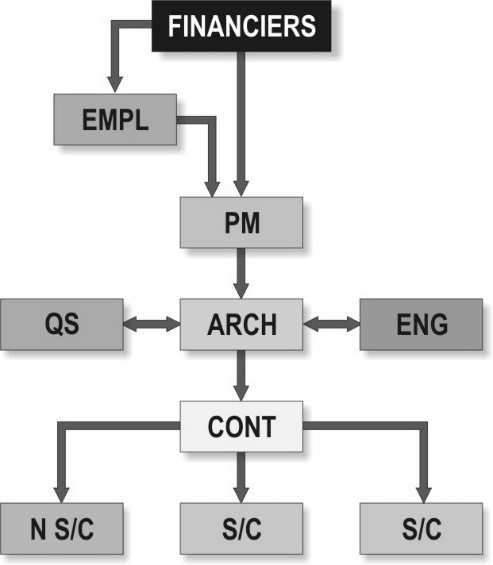

The essential difference between “construction management” and “management contracting” is in the relationship between the contracting parties. In “management contracting” the construction manager is in direct contract with the works or trades contractors who carry out the works contracts. In “construction management” on the other hand, the construction manager does not himself contract with the works contractor. In ‘construction management” as illustrated below the Employer/Owner directly employs all the works contractors and provides the coordination of management through a consultant construction manager, leaving the Employer/Owner itself to absorb the risks associated with the coordination.

| Communications | Contractual Nexus |

|  |

The construction manager may be a major contractor, but it is also entirely practical and efficient for the management of the separate trades to be undertaken by the architect, engineer or quantity surveyor. A major feature of this approach is the way in which it elevates the status of the works contractors to a major participating role, thereby recognizing their complete involvement with design, construction and programming in their particular specialization.

Under this structure the Employer/Owner employs a number of works contractors, of the size and specialization that would be appropriate for subcontractors under a traditional main contract. The Employer/Owner is therefore effectively its own main contractor and has responsibility for finding and tendering the works contract packages and coordinating the performance of the work. Unless the Employer/Owner has the in-house expertise, in addition to the usual professionals, it must also employ a construction manager or one of the design team to manage the works contractors and coordinate the works on its behalf.

The increased risk for developers involved in contracting with and coordinating a large number of works contractors is attributable to the fact that, because the separate contract values tend to be quite low in proportion to the total project value, liquidated damages for delay payable by the works contractors (which, for commercial reasons, should not be disproportionately high in relation to the contract value) will tend to be less than under a traditional main contract. On the other hand, the advantages of this form of procurement include:

The practical difficulties in this form of procurement are associated with:

In particular, the combination of factors 2 and 3 above presents problems of a conceptual nature, but these are rather more easily solved in practice than in theory.

The programme to which each works contractor is to work must have contractual status for the construction management system to work. If the works contractor is simply given a date by which its works must be completed, but it is left to the works contractor as to how it achieves this completion date, it will be very difficult for the construction manager to control the progress and integration of the works contractor’s work (e.g. to have works contractors working contemporaneously), and the “fast track” benefits of construction management will be jeopardized.

Thus, the programme must in fact be the “developer’s programme” and be designed by the construction manager to sequence each works contractor’s package. The works contractors cannot be given the power to coordinate their work amongst themselves: not only do they generally lack the practical ability to oblige each other to work in certain sequence or on certain parts of the site, but because of the intermittence of their interest they cannot have command of the overall concept of how each part of the project fits together. In so far as it is the construction manager’s task to programme the works contractors, the control of the works contractor ( to ensure that the works contractor does not delay other works contractors) must come about as a result of the works contractor’s participation in the programme and its acceptance of its part in it as a contractual obligation ( in this respect the programming and integration requirements are no different from the procedures that the contractor should adopt in regard to its domestic subcontractors and nominated subcontractors under traditional forms of contract.)

There are several minor works agreements that are suitable for a works contractor in this form of procurement. There is no need here for more complicated forms of dealing with complex interrelationships and long contract periods, since the works contractors are only required to perform discrete parts of a project (generally their particular trades only)

Liquidated damages are the normal sanction, but there is a risk that the damages leviable against a particular works contractor will not represent the Employer/Owner’s likely loss in the event of late completion of the project as a whole. In this method the problem is that, except in periods of economic depression, a works contractor, say for tiling with a contract value of $ 400,000, is unlikely to consider entering into a contract for the completion of an office building which will justify liquidated damages of $ 200,000 per week in the event of non-completion.

In this form of procurement, the “flexibility” and the attendant benefits of reduced cost and enhanced quality make this an attractive alternative to the traditional “build only” method of procurement.

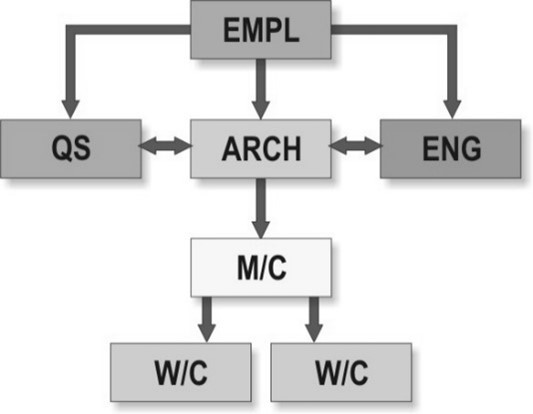

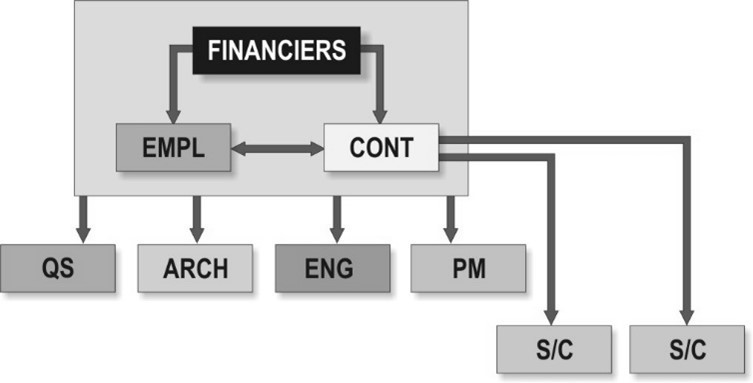

“Management contracting” is a procurement process used, so far as construction is concerned, where the Employer/Owner has a contract only with the management contracting firm. This contracting construction management firm then enters its own contracts with the works contractors doing the work. This is to be distinguished from the term “construction management” in which the Employer/Owner enters into direct contracts with the works contractors actually doing the work. The communications and the contractual responsibilities are illustrated below. There is, at present, considerable confusion over the use of these terms, and unfortunately, “management contracting” is frequently used to refer to both procurement patterns of the construction stage.

| Communications | Contractual Nexus |

|  |

Under this structure the Employer/Owner will employ the professionals to design the facility and the management contractor to construct it. This is similar to a traditional structure except in the case of the risk of default by subcontractors (known as works or trade contractors) which under this form of procurement is borne by the Employer/Owner, and not by the management contractor. In other words, it is somewhat like the traditional form of “build only” procurement method but with a guaranteed profit for the contractor with limited responsibility, even for domestic subcontractors.

The relationship between risk and tender premiums was a critical factor in the emergence of “management contracting” as a method of project procurement. In a technologically sophisticated development project, the contractual risks for the contractor can lead to unrealistically inflated tenders. The theory behind this form of procurement is thus that the Employer will be in a strong position to bear the risk, especially if the Employer is a property developer who builds frequently. It is an established principle of risk assessment that, where the Employer builds frequently and has large resources, the uncertainty associated with contractual risk is reduced. However, it is not so much that the risk is reduced, but the uncertainty of the risk factor occurring is reduced. Indeed, the likelihood of a risk factor occurring (such as delay or escalation of cost) is greater to a habitual developer. This method of procurement is often encouraged on the basis that if the risk is almost certain to occur, it is meaningless to pay someone else to adopt it. And it is this philosophy which is employed to justify the choice of a contract form which used to be said to eliminate risk to the contractor.

The usual mechanism is that the management contractor is paid a fee together with all amounts due to the works contractors under the works contracts. Although it can require competitive tendering of the works’ contract packages and can approve the terms of the works contracts, the risk of failure of coordination by the management contractor can give rise to delays, claims by works contractors and escalation of the cost of the works the risk of which resides with the Employer, unless it can show that the loss which the works contractor has suffered has arisen as a breach by the management contractor. There can be significant difficulty in obtaining redress from a management contractor.

It used to be a common misconception of management contractors that management contracting was a risk-free enterprise and that all it had to do was management, a quasi-professional task. Management contractors also assumed that, so long as they tried their professional best, they could expect to be paid on a cost-plus basis. So, where it says in the management contract: “ensure the regular and diligent progress” and “secure the completion of the same on or before the completion date”, the words “ensure” and “secure” really mean no more than use best endeavors. Since all delays caused by the works contractors were beyond the control of the management contractor, they therefore allowed the management contractor an extension of time without liability. In Mowlem v Eagle Star the ruling was that to become entitled to an extension of time the delay by the works contractor had to be beyond the control of both the works contractor and the management contractor. In practice, redress will depend largely on what indemnities are given by the respective works contractors to the management contractor.

The advantages of the structure are similar to those of construction management in that the works contracts can be entered into after settlement of the management contract, as and when the project programme requires. There is also the similar disadvantage to working under a traditional main contract, even when the contract has a fixed price, as liquidated damages for delay are likely to be less per works contract than the total liquidated and ascertained damages. In the past the completion of collateral warranties with each of the works contractors was the normal way of dealing with this.

Main influences on site times in management contracting were found in studies to be much the same as with other means of procurement, save that there appeared to be an enhanced risk in regard to default through:

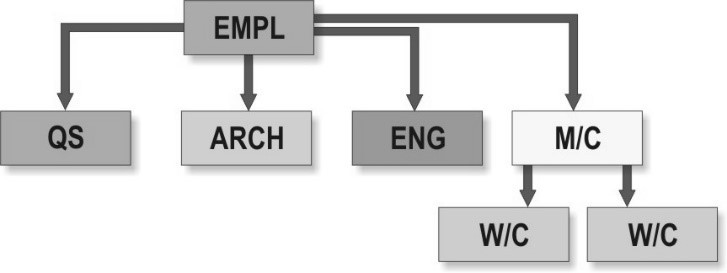

Under what is alternatively called Private Finance Initiative (PFI) or Public Private Partnership (PPP), a government typically grants a concession to a developer under which the developer has the obligation to build and, for a fixed period, operate the facility (for instance, prison, road, tunnel, bridge, water or other public or large-scale services). The developer usually finances the development, either from one bank or a syndicate of banks and the loans are repaid from tariffs paid by the state or the users of the facility over the life of the concession. At the end of the concession period the facility is usually expected to be transferred into state ownership.

In this method of procurement, the developer can thus be a concession company, the shareholders of which comprise a construction company, one or more financiers, and possibly a local interest or other shareholders in the equity. The financiers will expect to share with the other shareholders some construction or operational risk but may require some protection against political risk, such as a change in local law which might result in the project becoming non-viable as a private development.

Apart from the political risk, the other major problem in this form of procurement arises out of the relationship of the shareholders in the development concession company. If the development is a joint venture and one of the joint venturers is a contractor (who will owe duties to that company) then the other joint venturers will be concerned to ensure that the subsidiary contracts are at arm’s length. They will also be concerned to see that the contracts are monitored and enforced on an entirely impartial basis.

| Communications | Contractual Nexus |

|  |

Thus in a 50/50 joint-venture company, a bank for example, should not be able to block action by the developer or contractor in relation to a claim under the relevant construction contract. This could be achieved by providing that the directors nominated by the contractor-joint-venturer are not entitled to vote on the relevant resolution, or by ensuring that for these matters at least there are independent directors who will, if required, provide a majority vote binding on the development company. It will also be important to ensure that a single joint-venturer cannot prevent a company meeting from being held to deal with these matters.